Reven Pharmaceutical’s Response

Questions or comments? Write us here: [email protected]

Access and download Reven’s complete filing here.

Text Formatted Version Available Below

—

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 1 of 51

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO

Civil Action No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-KLM

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND

EXCHANGE COMMISSION,

Plaintiff,

v.

REVEN HOLDINGS, INC. d/b/a REVEN

PHARMACEUTICALS, REVEN

PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., BRIAN D.

DENOMME, PETER B. LANGE, and MICHAEL A.

VOLK,

Defendants,

and

REVEN, LLC, REVEN IP HOLDCO, LLC, REVEN

ONCOLOGY LICENSING, LLC, and HEALTH

ANALYTICS & RESEARCH SERVICES, LLC,

Relief Defendants.

DEFENDANTS’ AND RELIEF DEFENDANTS’

OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 2 of 51

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page(s)

INTRODUCTION - pg 1

BACKGROUND - pg 5

LEGAL STANDARD - pg 12

ARGUMENT - pg 13

- The SEC has not made a clear showing of misappropriation. - pg 13

- The Reven Principals’ employment agreements and other benefits. - pg 14

- The SEC’s flawed analysis does not support its misappropriation

claims. - pg 16

- The SEC has not made a clear showing that Defendants made material

misstatements or omissions with scienter. - pg 19

- Legal Standard - pg 20

- The SEC failed to meet its burden to clearly show a violation to

justify a preliminary injunction for each of Defendants’

challenged statements - pg 22

- Defendants’ challenged statements as to compensation

were not material and not made with scienter. - pg 23

- Statements regarding preparing to take Reven public. - pg 27

- Statements regarding use of funds. - pg 34

- iv. Statements regarding Florida litigation. - pg 38

- The SEC has not made a substantial showing that any violation of the

Securities Laws is likely to recur. - pg 42

CONCLUSION - pg 43

i

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 3 of 51

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

Cases

Aaron v. SEC,

446 U.S. 680 (1980) ................................................................................................ 12

City of Philadelphia v. Fleming Cos, Inc.,

264 F.3d 1245 (10th Cir. 2001) .................................................................... 4, 21, 22

Correa v. Liberty Oilfield Servs., Inc.,

548 F. Supp. 3d 1069 (D. Colo. 2021) ..................................................................... 22

Dronsejko v. Thornton,

632 F.3d 658 (10th Cir. 2011) ................................................................................ 22

Grossman v. Novell, Inc.,

120 F.3d 1112 (10th Cir. 1997) .................................................................. 20, 21, 22

Indiana Pub. Ret. Sys. v. Pluralsight, Inc.,

45 F.4th 1236 (10th Cir. 2022) ............................................................................... 21

In re Level 3 Commc’ns, Inc. Sec. Litig.,

667 F.3d 1331 (10th Cir. 2012) .............................................................................. 21

SEC v. Cell>Point, LLC,

No. 21-CV-01574-PAB-KLM, 2022 WL 444397 (D. Colo. Feb. 14,

2022) ...................................................................................................... 12, 20, 23, 42

SEC v. Compania Internacional Financiera S.A.,

No. 11-cv-4904, 2011 WL 3251813 (S.D.N.Y. July 29, 2011) .......................... 13, 42

SEC v. Cooper,

142 F. Supp. 3d 302 (D.N.J. 2015) ................................................................... 18, 19

SEC v. Curshen,

372 F. App’x 872 (10th Cir. 2010) .................................................................... 12, 20

SEC v. Goldstone,

952 F. Supp. 2d 1060 (D.N.M. 2013) ................................................................ 20, 25

SEC v. Haswell,

654 F.2d 698 (10th Cir. 1981) .................................................................................. 4

ii

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 4 of 51

SEC v. Scoville,

913 F.3d 1204 (10th Cir. 2019) .......................................................................... 4, 12

SEC v. Traffic Monsoon, LLC,

245 F. Supp. 3d 1275 (D. Utah 2017) .................................................................... 13

SEC v. Unifund SAL,

910 F.2d 1028 (2d Cir. 1990) .................................................................................. 12

Statutes

Exchange Act Section 10(b) .................................................................................. passim

Securities Act Section 17(a)(2) .................................................................. 12, 13, 19, 20

Other Authorities

SEC Rule 10b-5 .......................................................................................... 12, 13, 19, 20

iii

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 5 of 51

INDEX OF EXHIBITS TO BRIEF

Ex No. | Exhibit Letter to Declaration | Description |

1 | Declaration of Jon S. Ahern, CPA, CGMA | |

2 | Declaration of Michael A. Volk | |

| A | Executive Employment Agreement for Michael Volk dated March 15, 2019 |

| B | Executive Employment Agreement for Peter Lange dated March 15, 2019 |

| C | Executive Employment Agreement for Brian Denomme dated March 15, 2019 |

| D | Executive Employment Agreement for Michael Volk dated March 15, 2020 |

| E | Executive Employment Agreement for Peter Lange dated March 15, 2020 |

| F | Executive Employment Agreement for Brian Denomme dated March 15, 2020 |

| G | Executive Employment Agreement for Brian Denomme dated March 15, 2021 |

| H | Executive Employment Agreement for Michael Volk dated March 15, 2021 |

| I | Executive Employment Agreement for Peter Lange dated March 15, 2021 |

3 | Declaration of Peter Lange | |

4 | Declaration of Bill Luther | |

5 | Declaration of Geoff Leopold | |

6 | Declaration of Henk Van Wyk | |

7 | Declaration of Katherine Preston | |

| A | Complaint for Damages with Demand for Jury Trial – Florida Litigation |

| B | First Amended Complaint – Florida Litigation |

| C | Order Adopting Recommended Order – Florida Litigation |

| D | Second Amended Complaint – Florida Litigation |

| E | Corrected Third Amended Complaint |

| F | Order on Exceptions to Recommended Order of General Magistrate – Florida Litigation |

| G | Fourth Amended Complaint – Florida Litigation |

iv

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 6 of 51

| H | Discovery Responses provided by the Defendants |

| I | Leah Schaatt Deposition Excerpts |

| J | Lee-Ann Frost Deposition Excerpts |

| K | Rodell Rudolph Deposition Excerpts |

| L | Brian Denomme Deposition Excerpts |

| M | Leah Schaatt Deposition Exhibit 7 |

| N | Leah Schaatt Deposition Exhibit 8 |

| O | Leah Schaatt Deposition Exhibit 9 |

| P | Frost Text Messages |

v

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 7 of 51

INTRODUCTION

Earlier this year, the SEC persuaded this Court on an ex parte basis to enter a temporary restraining order (ECF No. 28) that included onerous restrictions and a wide-ranging, deleterious corporate and personal asset freeze, all premised on the SEC’s theory that Defendants had “bilked investors out of over $8.8 million” and “misappropriated” these funds for their own personal use (ECF No. 3 at 1). The SEC’s premise was—and is—not only unfounded but demonstrably false.

Indeed, as a threshold matter and as detailed in the expert declaration of Jon Ahern of Alvarez & Marsal, a leading forensic accounting investigations expert, Reven’s Principals were owed far more in unpaid compensation than the SEC now accuses them of having “misappropriated.” In fact, for the three-year period on which the SEC bases its allegations, Reven’s Principals were (combined) owed $23.25 million in compensation—significantly more than even the mistaken and inflated amounts the SEC asserts they received. And those figures do not even account for the Reven Principals’ decisions to defer compensation and allow Reven to reserve cash, invest in the company, and continue to progress on the path toward commercializing Rejuveinix (“RJX”), a life-changing technology dedicated to assisting patients with critical limb-threatening ischemia, sepsis, and other ailments often associated with an underlying condition of chronic inflammation.

In the face of initial scrutiny, the SEC’s allegations of misappropriation havealso begun to crumble in other respects. Alvarez & Marsal’s preliminary investigation shows that roughly half of the purportedly “misappropriated” funds were not, as the SEC represented, “for the benefit of Reven’s Principals but rather for

1

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 8 of 51

Reven business purposes.” Ex. 1, Decl. of Jon Ahern, ¶ 7. For example, the SEC’s prior proffer to this Court incorrectly assumed that almost $4.7 million in payments to American Express were made for the personal benefit of the Reven Principals. That is demonstrably not the case. Contemporaneous records show “that most of the American Express activity was for Reven business purposes, including charges by other Reven employees (non-Reven Principals) and charges for marketing, research [and] development, office expenses, travel, and other Reven expenses.” Id.

What’s more, during this period, the Reven Principals continued to contribute and devote even more of their own personal assets (on top of investor funds) toward the continued development of RJX, in an effort to bring this life-changing drug through clinical trials and to market, with the goal of eventually finding a profitable exit opportunity for Reven’s shareholders. Those promising efforts were brought to a screeching halt following the SEC’s institution of this action and the resulting TRO.

So what happened here? The SEC, unfortunately, appears to have been led astray by a small group of disgruntled and entrepreneurial Reven investors who, initial discovery confirms, have (a) little, if any, first-hand knowledge of the alleged facts on which the SEC bases its claim of misappropriation, but more troublingly, (b) their own ulterior motives to tie up Reven and its Principals in protracted litigation in the hope of appropriating Reven’s intellectual property and creating a competing business. Indeed, it turns out that the SEC’s key witnesses have been coordinating in this regard for over a year with Reven’s disgruntled former Chief Technology Advisor, Dr. James Ervin. See Ex. 7, Decl. of Katherine Preston, Ex. I, Deposition of

2

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 9 of 51

Leah Schaatt Transcript, 142:13–21; Ex. 6, Decl. of Henk van Wyk, ¶¶ 6–11. This group has gone so far as to repeatedly (unsuccessfully) pressure Reven’s Chief Scientist and the inventor of RJX, Henk van Wyk, to destroy information on his Reven-issued computer, in direct violation of this Court’s TRO. See van Wyk Decl. ¶ 12.

Simply put, the case the SEC put forward behind closed doors and without adversarial scrutiny does not hold up, and in fact, bears little resemblance to reality. Expert accounting analysis confirms that there has been no misappropriation, and the baseless accusations to the contrary—on which this lawsuit rests and the TRO relies—come from vague allegations by self-interested sources with clear ulterior motives who should not be credited.

Nor does the evidence support the SEC’s fallback assertions that Defendants made material misrepresentations or omissions to investors. As demonstrated below, many of the purported “misstatements” the SEC identifies were accurate statements of present fact or otherwise accurately reflected Defendants’ good-faith belief and state of mind at the time the statements were made. Other statements that the SEC challenges, meanwhile, are (a) more generalized, forward-looking expressions of Defendants’ optimistic expectations for the company, which courts have routinely held are immaterial, or (b) at most, unintentionally incomplete assertions that, in the context of other disclosures and information that was readily available, were not the type of information on which reasonable investors would rely.

3

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 10 of 51

Further, even if the SEC could establish any material misstatement or omission (and it cannot), its request for an injunction would still fail because the SEC has not clearly shown the separate element of scienter. Scienter requires a showing of an “intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud,” in other words, “knowing or intentional misconduct.” City of Philadelphia v. Fleming Cos., Inc., 264 F.3d 1245, 1261 (10th Cir. 2001). Though certain egregiously reckless conduct tantamount to actual knowledge or intent may support scienter, courts in this circuit are “cautious about imposing liability for securities fraud based on reckless conduct,” and simply having “knowledge of facts that are later determined by a court to have been material, without more, is not sufficient.” Id. at 1260. Here, any purported misstatement or omission, in addition to being immaterial, was at most the product of simple negligence, not deliberate fraud. The lack of any knowing or reckless violation “bears heavily” against the SEC’s requested injunction. SEC v. Haswell, 654 F.2d 698, 699 (10th Cir. 1981).

In short, the SEC has not made a “clear showing” that it is likely to prove its claims of securities fraud against Defendants—far from it—let alone that there is a substantial likelihood that such purported violations of the securities laws are likely to recur. SEC v. Scoville, 913 F.3d 1204, 1213 (10th Cir. 2019). In the meantime, the ex parte asset freeze that was ostensibly intended to “preserv[e] existing investor assets,” ECF No. 3 at 2, has had the exact opposite effect—threatening Reven’s ability to maintain its existing intellectual property and other assets, wasting valuable patent life, and blocking Reven’s ability to move forward with critical drug trials and

4

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 11 of 51

a possible public offering, thereby decimating (not preserving) investor assets. For these reasons and those elaborated on below, the current TRO and asset freeze should be lifted, and the SEC’s motion for a preliminary injunction should be denied in its entirety.

BACKGROUND

Reven’s History and Operations

Reven is a group of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies with a singular purpose of developing pharmaceutical assets, and it has seen significant growth over the past two decades. Reven’s corporate history extends back to at least 1999. See ECF No. 78, § 4.i. Reven’s primary focus has been developing and commercializing a cardiovascular and anti-inflammatory intravenous drug treatment called Rejuveinix (“RJX”). Id. § 4.a.

The Reven structure includes multiple entities. Reven Holdings, Inc., the parent entity, is now a Delaware corporation with its principal place of business in Westminster, Colorado. Id. § 4.a. Reven Holdings was formed in August 2018 as a privately held biotechnology and pharmaceutical holding company. Id. Reven, LLC is a Delaware limited liability company formed in August 2018, also with its principal place of business in Westminster, Colorado. Id. § 4.f. Reven, LLC is a wholly owned subsidiary of Reven Holdings and functions as the holding company’s operating arm. Id.1 Reven IP Holdco LLC is also a Delaware LLC with its principal place of business in Westminster, Colorado, and holds assets. See id. § 4.g.

1 Reven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. was a Florida corporation formed in October 1999. Id. § 4.b. In August 2018, Reven Pharmaceuticals transferred its assets, including its intellectual property relating to RJX,

5

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 12 of 51

Reven’s business operations have been mainly managed by three executives: Peter Lange (Chief Executive Officer), Brian Denomme (President and former Chief Operating Officer), and Michael Volk (Chief Strategy Officer and former Chief Financial Officer).2 Id. §§ 4.c-e. All three are co-founders and members of Reven’s Board of Directors. Id. They are also the three largest shareholders in Reven. Id. §§ 4.n-o. Together, the Reven Principals have brought in thousands of investors to the company. Each is passionate about Reven and deeply committed to its mission of bringing potentially life-changing therapies to the public. To advance this goal, they have consistently put the interests of the company first, often (and increasingly in recent years) deferring their own pay so that Reven can continue to progress.

That progress over the past several years has occurred at an astonishing rate. By 2021, Reven had 12 patents granted in two families in the United States, with applications made for 28 patents in five families; globally, Reven had been issued 21 patents, with 98 other applications in the filing, application, and prosecution process. See Ex. 2, Decl. of Michael Volk, ¶ 2. Reven had completed 30+ pre-clinical animal studies, 13 published articles, six peer-reviewed publications, and seven clinical white papers, and developed over 50 protocols. Id. ¶ 3. The FDA had approved two Phase 2 investigational new drug applications, the European Medicines Agency had approved Phase 2 human trials, and Reven had completed Phase 1 human trials in Australia and the United States for its breakthrough drug, RJX. Id. By November

to Reven, LLC. Id. § 4.f. Reven Pharmaceuticals was administratively dissolved in September 2019. Id. § 4.b.

2 We refer to Mr. Lange, Mr. Denomme, and Mr. Volk collectively as the “Reven Principals.”

6

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 13 of 51

2021, Phase 2 human trials were 75% completed in the U.S., and Reven had met with dozens of investment banks and financial institutions regarding a public offering. Id. ¶ 4.

This Case Halts Reven’s Progress in its Tracks

Unfortunately, this action halted all of this revolutionary progress. The SEC notified Reven of its investigation in November 2021. This litigation started on December 9, 2022, when the SEC filed a sealed complaint seeking “emergency enforcement” to “stop an ongoing offering fraud and misappropriation of investor assets,” (ECF No. 1 ¶ 1) and an ex parte emergency motion for a temporary restraining order and asset freeze (ECF No. 3).

In its filings, the SEC attempted to persuade this Court that an emergency TRO was necessary by mischaracterizing standard organizational choices made by Defendants and various business-related expenses to suggest the existence of a fraudulent scheme. The SEC also alleged that Defendants made several misstatements in communications to investors. As demonstrated below, however, none of these alleged misrepresentations were material, let alone made with the requisite state of mind to support an injunction. Nor, when viewed in context with other available information and disclosures, were these statements even inaccurate or misleading. For instance, consistent with prior materials provided by the company, Reven’s July 6, 2020 Private Placement Memorandum (“PPM”) explained that Reven “extend[s] to each prospective investor . . . the opportunity, prior to its purchase of Shares, to ask questions of and receive answers from [Reven] concerning the Offering

7

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 14 of 51

and to obtain additional information . . . in order to verify the accuracy of the information set forth herein”; that Reven had “broad discretion in the use of proceeds” invested; and that the PPM contained “forward-looking statements” that “involve assumptions and describe our future plans” with “no assurance[s] that the forward

looking statements contained in this [PPM] will in fact occur.” ECF No. 7-14 at 2, 6; ECF No. 7-15 at 13.

Central to the SEC’s allegations was the contention that the Reven Principals understated their compensation for three years—2019, 2020, and 2021—in the company’s PPMs. But the SEC ignores the Reven Principals’ employment agreements, which were available to Reven investors and detailed the specific amount that could be earned both in base compensation and annual target bonuses. Volk Decl., Exs. A-I. These bonuses were tied to specific metrics regarding Reven’s progress and goals, 58 out of 59 of which the Reven Principals achieved from 2019 to 2021 (and the remaining metric was partially met). Volk Decl. ¶ 6. In reality, the Reven Principals took significantly less compensation than they were entitled to under their employment agreements and often contributed their own money to the company to pay vendors and employees. Ahern Decl. ¶¶ 31-35; see also ECF No. 54, Ex. A to Reven Entities’ Decl., at e.g., 2, 5, 8, 10. Unaware of these facts, this Court granted the SEC’s ex parte motion and ordered a temporary restraining order and asset freeze. ECF No. 28.

Despite a few small modifications made to the temporary restraining order and asset freeze (ECF Nos. 72, 74), the SEC’s actions have created punishing burdens for

8

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 15 of 51

Reven, its employees, and its shareholders. Reven’s substantial growth and once near-complete FDA trials are languishing without progress, and much of the data generated by Reven in previous trials will need to be duplicated. Volk Decl. ¶ 27. And much of the experienced and knowledgeable staff that were previously devoted to Reven’s clinical trials and development of intellectual property have departed given Reven’s inability to raise money and pay salaries. Id. ¶ 28. Vendors have also severed ties, and Reven has lost substantial credibility with existing investors, potential future investors, as well as, critically, the FDA. Id. Perhaps most importantly, Reven’s current investors and shareholders are in limbo as they watch a company they believed in slowly suffocate.

Discovery Reveals Ulterior Motives from Key Witnesses

Recently, Reven has also discovered that the genesis of this action may in large part owe to the clandestine efforts of a small group of self-interested investors (including at least two of the SEC’s principal witnesses, Leah Schaatt and Lee-Ann Frost) who have apparently been working together with Reven’s disgruntled former Chief Technology Officer, Jim Ervin,3 to hamstring Reven in a legal morass while misappropriating Reven’s intellectual property in an effort to form a competing business venture.

3 Reven terminated Ervin’s employment in August 2020. See Volk Decl. ¶ 24. Ervin sued Reven in February 2021 for failure to pay compensation allegedly owed to him. Id. In the fall of 2021, when mediation proved unsuccessful, Ervin threatened to file a complaint with the SEC. Id. ¶ 25. A short time later, Reven received notice of the SEC’s investigation. Id. Ervin’s suit against Reven is ongoing. Id. ¶ 24.

9

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 16 of 51

In particular, testimony and documentary evidence show that, as early as May or June 2022, Schaatt and Frost had hatched a plot to usurp Reven’s management or intellectual property. See van Wyk Decl. ¶ 6. To that end, right after the Reven Principals convened a Zoom call on October 6, 2022 to communicate to a small group of Reven’s largest investors that the company was in dire financial straits, Frost sent Schaatt a text message proposing that they “put together a good team” to “intervene.” Preston Decl. Ex. P, Frost Text Messages, FROST_0595–98; see also Schaatt Tr. at 136:21–137:22 (testifying that she exchanged texts with Frost between October 6, 2022 and October 10, 2022). Schaatt responded suggesting that they “make a plan to move forward,” noting that they would “need time and good legal counsel[,] [a]nd money, of course.” Frost Texts, FROST_0597–98. Just days later, on October 15, 2022, Schaatt reached out to the SEC for the first time and after that began working with the SEC, together with Frost, as its principal witnesses in this proceeding. See Schaatt Tr. 126:9–128:8.

At the same time they were working with the SEC to provide the testimony that would form the backbone of the Commission’s ex parte application for a TRO and asset freeze, Schaatt and Frost were actively working with Ervin to develop a competing business venture that would ultimately become known as Veterinary Nutraceuticals. See van Wyk Decl. ¶¶ 6–8, 10; see also Preston Decl. Ex. J, Deposition of Lee-Ann Frost Transcript, 205:13–22. As contemplated in their earlier text messages, Schaatt and Frost retained IP counsel to explore Veterinary Nutraceuticals’ “freedom to operate” around Reven’s intellectual property. See

10

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 17 of 51

Schaatt Tr. at 151:3–15; Frost Tr. at 203:21–204:19. By early 2023, Ervin was actively misappropriating Reven’s intellectual property, see Preston Decl. Exs. M–N, Schaatt Dep. Exs. 7–8; van Wyk Decl. ¶ 11, and had attempted to recruit Reven’s Chief Scientist, Henk van Wyk, and Reven’s Head of Quality Assurance, Mariette van Wyk, to participate in the new venture, see van Wyk Decl. ¶¶ 7, 9. Ervin also developed a full-blown business plan that made clear that Schaatt and Frost were to provide “[c]apital” and “business plan review and oversight” to Veterinary Nutraceuticals in exchange for 25% of the new venture’s “stock” and “profit split.” See Preston Decl. Exs. M, O, Schaatt Dep. Exs. 7, 9. And as part of his pitch, Ervin even told Mr. and Mrs. Van Wyk that Reven and its Principals would be “tied up” by the SEC’s present enforcement action for years, unable to thwart their hostile efforts. See van Wyk Decl. ¶ 9.

Tellingly, at or around the time that Defendants served document and deposition subpoenas on Schaatt and Frost, Ervin contacted Mr. and Mrs. van Wyk and asked them to delete documents and communications related to Veterinary Nutraceuticals from their Reven-issued laptops in direct violation of this Court’s TRO. See van Wyk Decl. ¶ 12. Schaatt also testified that Ervin called her the day before her deposition in this action to warn her that he was concerned that the Reven Principals had gotten wind of Veterinary Nutraceuticals. See Schaatt Tr. at 161:3-12. And Frost testified that she put her efforts related to Veterinary Nutraceuticals on hold while she focused on “getting past these depositions,” but conceded that “lots can happen after we’re finished being deposed.” See Frost Tr. at 205:23–209:4.

11

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 18 of 51

This further undermines the SEC’s allegations and underscores that the excessive relief previously granted was unwarranted.4

LEGAL STANDARD

To obtain the requested preliminary injunction, the SEC must make a “clear showing” that a violation of the securities laws has occurred and a “substantial showing that the violation is likely to occur again.” SEC v. Cell>Point, LLC, 2022 WL 444397, at *5 (D. Colo. Feb. 14, 2022). When the SEC seeks an injunction that will “alter the status quo,” the agency “must meet a heightened burden” and “make a strong showing both with regard to the likelihood of success on the merits and with regard to the balance of the harms.” Scoville, 913 F.3d 1204 at 1214; see also SEC v. Unifund SAL, 910 F.2d 1028, 1039 (2d Cir. 1990) (“[A] district court, exercising its equitable discretion, should bear in mind the nature of the preliminary relief the Commission is seeking, and should require a more substantial showing of likelihood of success, both as to violation and risk of recurrence, whenever the relief sought is more than preservation of the status quo.”).

In assessing the risk of any recurrence of an alleged securities violation, “the degree of scienter ‘bears heavily’ on the decision.” SEC v. Curshen, 372 F. App’x 872, 882 (10th Cir. 2010) (quoting SEC v. Pros Int’l, Inc., 994 F.2d 767, 769 (10th Cir. 1993)). Thus, “[a] knowing violation of §§ 10(b) or 17(a)(1) will justify an injunction more readily than a negligent violation of § 17(a)(2) or (3).” Id.; see also Aaron v. SEC, 446 U.S. 680, 701 (1980) (“As the Commission recognizes, a district court may

4 Additional facts related to each of the SEC’s individual contentions are set forth in the Argument section below.

12

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 19 of 51

consider scienter or lack of it as one of the aggravating or mitigating factors to be taken into account in exercising its equitable discretion in deciding whether or not to grant injunctive relief. And the proper exercise of equitable discretion is necessary to ensure a nice adjustment and reconciliation between the public interest and private needs.”). In making this determination, courts should also consider the hardships resulting from an asset freeze and appreciate that “[t]he reputational and economic harm of suffering a preliminary injunction, especially on charges of fraud, can also be severe.” SEC v. Compania Internacional Financiera S.A., 2011 WL 3251813, at *10 (S.D.N.Y. July 29, 2011); see also SEC v. Traffic Monsoon, LLC, 245 F. Supp. 3d 1275, 1297 (D. Utah 2017) (stating the preliminary injunction would be “particularly burdensome” to the defendant’s business operations and “would certainly harm the continuing viability of the enterprise”).

Here, as demonstrated below, the SEC cannot meet its burden to obtain the requested preliminary injunction. Accordingly, the SEC’s motion should be denied, and the TRO and asset freeze should be lifted.

ARGUMENT

I. The SEC has not made a clear showing of misappropriation. The SEC alleges that Defendants violated Section 10(b), Rule10b-5, and Section 17(a)(1) and (3) by (1) making false and misleading statements to prospective investors and (2) engaging in deceptive conduct, including misappropriating investor funds. We begin with the latter because the SEC’s allegations and request for an injunction largely hinge on the flawed assertion that Defendants “misappropriated at least $8.8 million in investor funds.” ECF No. 3 at 1, 11–12, 35–36; see also ECF No.

13

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 20 of 51

28 at 3, 11. The SEC alleges that Defendants “misappropriated” funds through various means, including making payments directly to their personal bank accounts, paying personal credit cards, and transferring funds to other entities controlled by the Reven Principals. See ECF No. 3 at 1, 11-12, 35-36. But the SEC’s allegations do not withstand scrutiny.

A. The SEC ignores the Reven Principals’ employment

agreements and other benefit allowances.

Although the SEC chose to ignore many of these facts, the evidence now before the Court confirms that the Reven Principals used funds appropriately, consistent with what was approved by Reven’s Board of Directors, and in line with corporate formalities.

Between 2019 and 2021, Reven paid many business expenses using personal American Express cards owned by Mr. Volk and Mr. Denomme; Mr. Volk’s card also had several “sub-account” holders to simplify its use by other Reven personnel. See Ahern Decl. ¶ 15-16. Several employees—not just Mr. Volk or the other Reven Principals—had access to these cards and used them in the ordinary course of Reven’s operations. Id. Defendants’ independent accounting expert, Jon Ahern, analyzed Reven’s bookkeeping records and performed sampling to validate these facts. Id. ¶¶ 10-16.

Separately, as officers and directors working full-time for the company, the Reven Principals received compensation for their work. In particular, Reven entered into executive compensation agreements with each of the Reven Principals. See Volk Decl. ¶ 5 & Exs. A–I. These agreements provided for annual base compensation of

14

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 21 of 51

$900,000, $1,000,000, and $1,200,000 in 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively, for each of the Reven Principals.5 Id. In total, the employment agreements set forth base compensation equal to $3,100,000 for each Reven Principal from 2019 to 2021—or $9,300,000 in total for all three Reven Principals during this period. Id.; see also

Ahern Decl. ¶ 31. In addition, the employment agreements provided target bonuses of up to 150% of base salary if certain metrics were met, and all but one metric was met during the period from 2019 to 2021. Volk Decl. ¶ 6. The SEC is aware of these agreements and even attached some of them to its TRO Application. ECF No. 7 ¶¶ 33-35; ECF No. 3 at 7. These agreements, the associated board minutes, and other materials reflecting the Reven Principals’ compensation were at all times available to investors. Critically, however, the SEC’s key witnesses were far more concerned with product development than they were with executive compensation and thus never asked to see them. See Frost Tr. 85:5-86:16, 89:19-90:2, 123:13–18, 124:23–25, 182:11-18; Schaatt Tr. 27:7-24, 40:1-41:9, 53:4–25, 54:11–6, 170:5-15.

The SEC also mischaracterizes the related Health Analytics entity. Health Analytics was not, as the SEC baldly asserts, a “pass-through or shell company” that “provided no goods or services to Reven,” ECF No. 3 at 21; rather, it provided consulting services to both Reven and other entities. See Preston Decl. Ex. H, Defendants’ Discovery Responses, Response to Interrogatory No. 10. Health Analytics was also sometimes used, for tax purposes, to pay the Reven Principals (although, as further explained below, those payments never exceeded the amounts

5 The 2019 agreements initially state that annual compensation would be $750,000, but this is a mathematical error, as later provisions state that monthly compensation would be $75,000 per month.

15

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 22 of 51

the Reven Principals were entitled to receive under their compensation agreements). See, e.g., ECF No. 57-3 at 6, 7, 11; ECF No. 57-6 at 96. Far from the nefarious “shell” alleged by the SEC, Health Analytics was a legitimate company that was and would continue to be used for perfectly normal business purposes had the SEC not effectively halted its operation.

B. The SEC’s flawed analysis does not support its

misappropriation claims.

The SEC has failed to meet its burden to clearly show misappropriation of investor funds for at least three reasons.

First, the Court should not credit the SEC’s misappropriation claims because they are based on a flawed analysis. The $8.8 million figure advanced by the SEC improperly includes millions of dollars of payments that the evidence confirms were for the benefit of Reven and its legitimate business purposes—not the Reven Principals. In addition, the SEC’s figure does not accurately reflect the full compensation and benefits that the Reven Principals were entitled to receive from 2019 to 2021.

The SEC’s calculation of the alleged misappropriation stems from the Declaration of Donna Walker. See ECF No. 8. As part of her calculation, Walker included more than $4.6 million in payments to “American Express related to Volk’s personal credit card.” Id. ¶ 18.a. But, Walker incorrectly assumed that 100 percent of these payments were linked to Mr. Volk’s card and thus attributed them to his personal benefit. In response, Ahern based his assessment of any potential misappropriation on contemporaneous records and statements. As for the $4.6

16

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 23 of 51

million in payments to American Express, Ahern explains that there “were numerous users of the American Express account, each of whom appears to have had a separate card,” such that the assumption that these charges are all Mr. Volk’s “is neither fair nor accurate.” Ahern Decl. ¶ 15.

Walker’s estimates also fail to properly consider several other charges for legitimate business expenses, as well as properly charged travel allowances that the Reven Principals were entitled under their employment agreements for 2019 to 2021. After analyzing the company’s general ledger, assessing which of these expenses were reasonable and supported, sampling the remaining charges, and making other adjustments, Ahern concludes that Walker’s total estimated misappropriation figure is overstated by at least $4 million. Id. ¶ 30.

Ahern has also determined that Walker’s estimate did not reflect the full base compensation that the Reven Principals were entitled to receive for 2019 to 2021 under their employment agreements, which even before applying target bonuses, reduces the alleged “misappropriation” to approximately $1.58 million. Id. ¶ 32. And after applying target bonus amounts under their employment agreements, the purported $8.8 million is more than fully offset. Id. ¶¶ 34-35.

17

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 24 of 51

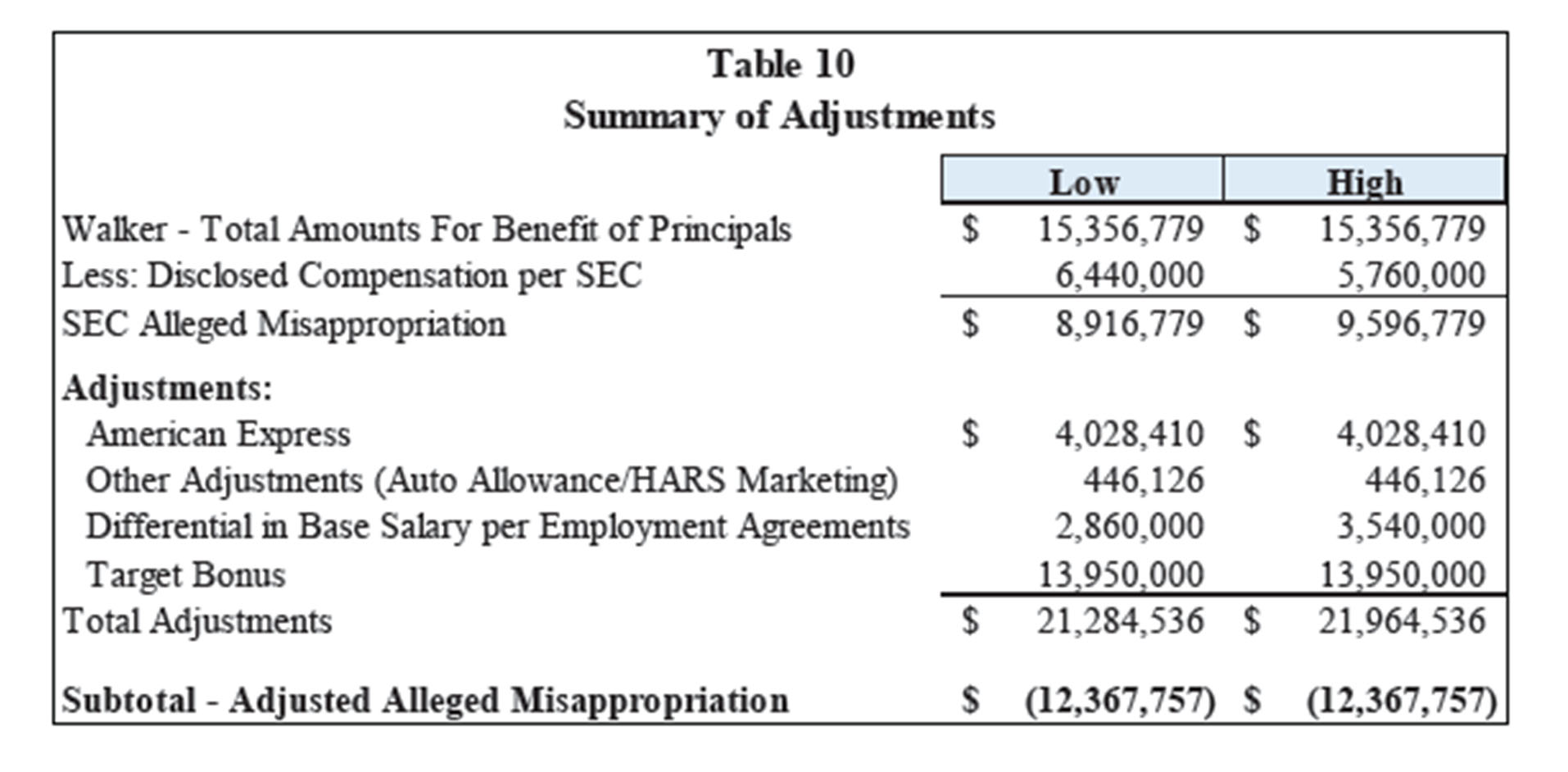

The following is a full summary of Ahern’s adjustments, confirming that there was in fact no misappropriation by Defendants:

Second, the SEC asserts that Defendants improperly transferred money to Health Analytics, claiming it was a “pass-through or shell company” used to transfer funds to the Reven Principals and that Health Analytics “provided no goods or services” to the company. ECF No. 3 at 21. However, Ahern’s initial analysis shows that at least some portion of the funds were used for Reven’s business purposes. Ahern Decl. ¶ 29. For example, Health Analytics used $275,000 of these funds for marketing by sponsoring the World Pro Ski Tour in 2020 and 2021, which renamed its championship to the “Reven Cup.” Id.

Second, the SEC asserts that Defendants improperly transferred money to Health Analytics, claiming it was a “pass-through or shell company” used to transfer funds to the Reven Principals and that Health Analytics “provided no goods or services” to the company. ECF No. 3 at 21. However, Ahern’s initial analysis shows that at least some portion of the funds were used for Reven’s business purposes. Ahern Decl. ¶ 29. For example, Health Analytics used $275,000 of these funds for marketing by sponsoring the World Pro Ski Tour in 2020 and 2021, which renamed its championship to the “Reven Cup.” Id.

Third, the SEC baselessly asserts that Defendants structured two bank accounts at the same bank to “funnel[] investor funds” as part of a “fraudulent scheme.” ECF No. 3 at 1, 36 (quoting SEC v. Cooper, 142 F. Supp. 3d 302, 316 (D.N.J. 2015)). In truth, Defendants simply had one account at Wells Fargo that was typically

18

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 25 of 51

used to receive and maintain funding from investors and a second account for the company’s operations. ECF No. 8 ¶ 3; Volk Decl. ¶ 22. There is nothing improper about structuring company funds this way, as the Cooper decision cited by the SEC demonstrates. In Cooper, the undisputed evidence showed that the defendant and his company “engaged in sham transactions” and deceived investors “to make it appear to investors that they were sending money to an independent escrow agent,” created a “fake escrow company” to receive investor funds, and forged “fake account statements to investors to make them believe that their money was sitting in an escrow account or that their investments were collateralized with cash.” Cooper, 142 F. Supp. 3d at 316. Here, in contrast, there is no evidence of anything approaching such a “fraudulent scheme.” Id.

For each of these reasons, the Court should reject the SEC’s assertion that Defendants misappropriated $8.8 million from Reven’s investors. And based on this additional evidence, the Court should withdraw its TRO and decline the SEC’s request for a preliminary injunction and continued asset freeze.

II. The SEC has not made a clear showing that Defendants made material misstatements or omissions with scienter.

The SEC also claims that Defendants made materially false and misleading statements and omissions in violation of Exchange Act Section 10(b), SEC Rule 10b 5, and Securities Act Section 17(a)(2). ECF No. 3 at 25-34. They didn’t. The record evidence now before the Court confirms that many of the claimed “misstatements” that the SEC has identified were either (a) accurate statements of fact, (b) statements that accurately reflected Defendants’ good-faith understanding at the time the

19

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 26 of 51

statements were made, (c) immaterial forward-looking or generalized statements of opinion reflecting Defendants’ optimistic expectations and targets for the company, or (d) at most, incomplete statements that, in the context of other disclosures, cautionary statements, and other information that was readily available, were not the type of information that was actually or reasonably relied upon by investors.

A. Legal Standard

To show a violation of Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5(b), “the SEC must prove that defendants made: (1) a misrepresentation or omission (2) of material fact, (3) with scienter, (4) in connection with the purchase or sale of securities, and (5) by means of interstate commerce.” Cell>Point, LLC, 2022 WL 444397, at *6 (quoting SEC v. Smart, 678 F.3d 850, 856 (10th Cir. 2012)). For Section 17(a)(2), the requirements are “almost the same; the primary difference between § 17(a) and § 10(b) lies in the element of scienter” because “negligence is sufficient for § 17(a)(2).” Id. (quoting Smart, 678 F.3d at 857). Still, as noted above, for the SEC to justify the broad injunctive relief it has requested here, a high degree of scienter is required— negligence is not sufficient. Curshen, 372 F. App’x at 882 (citing Pros Int’l, 994 F.2d at 769).

To demonstrate a misstatement or omission, the SEC “must,” as a threshold matter, “set forth an explanation as to why the statement or omission complained of was false or misleading.” Grossman v. Novell, Inc., 120 F.3d 1112, 1124 (10th Cir. 1997). “The statement or omission must not merely be false now; rather, it must have been false at the time that the document containing it was created.” SEC v. Goldstone, 952 F. Supp. 2d 1060, 1196 (D.N.M. 2013); see also Grossman, 120 F.3d at 1124

20

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 27 of 51

(“[T]here is no reason to assume that what is true at the moment plaintiff discovers it was also true at the moment of the alleged misrepresentation, and that therefore simply because the alleged misrepresentation conflicts with the current state of facts, the charged statement must have been false.”).

“It is [also] not enough for a defendant’s statement or omission to be false or misleading, it must also be material.” Indiana Pub. Ret. Sys. v. Pluralsight, Inc., 45 F.4th 1236, 1248 (10th Cir. 2022). A statement is material “if a reasonable investor would consider it important in determining whether to buy or sell stock, and if it would have significantly altered the total mix of information available to current and potential investors.” City of Philadelphia v. Fleming Cos., Inc., 264 F.3d 1245, 1265 (10th Cir. 2001). Courts “have distinguished between statements that are material and those that are mere puffing . . . not capable of objective verification.” In re Level 3 Commc’ns, Inc. Sec. Litig., 667 F.3d 1331, 1339 (10th Cir. 2012) (alteration in original); see also Grossman, 120 F.3d at 1119 (“[S]tatements classified as ‘corporate optimism’ or ‘mere puffing’ are typically forward-looking statements, or are generalized statements of optimism that are not capable of objective verification.”). Thus, “[v]ague, optimistic statements are not actionable because reasonable investors do not rely on them in making investment decisions.” Grossman, 120 F.3d at 1119. A second category of “forward-looking representations are also considered immaterial when the defendant has provided the investing public with sufficiently specific risk disclosures or other cautionary statements concerning the subject matter of the statements at issue to nullify any potentially misleading effect.” Id. at 1120. Under

21

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 28 of 51

this “bespeaks caution doctrine,” forward-looking statements are not considered material if “documents available to the investing public ‘bespoke caution’ about the subject matter of the alleged misstatement at issue.” Correa v. Liberty Oilfield Servs., Inc., 548 F. Supp. 3d 1069, 1083 (D. Colo. 2021). “At bottom, the ‘bespeaks caution’ doctrine stands for the unremarkable proposition that statements must be analyzed in context when determining whether or not they are materially misleading.” Grossman, 120 F.3d at 1120.

The SEC must also clearly show that Defendants acted with scienter. Scienter is “a mental state embracing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud” that includes “knowing or intentional misconduct.” Fleming Cos., 264 F.3d at 1258. While certain reckless conduct may also support a showing of scienter, it must be “conduct that is an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care, and which presents a danger of misleading buyers or sellers that is either known to the defendant or is so obvious that the actor must have been aware of it.” Id. at 1260. But courts have been “cautious about imposing liability for securities fraud based on reckless conduct” alone, and allegations of “fraud by hindsight” are not sufficient. Id.; Dronsejko v. Thornton, 632 F.3d 658, 668 (10th Cir. 2011) (“recklessness under section 10(b) is a particularly high standard”).

B. The SEC failed to meet its burden to clearly show a violation to justify a preliminary injunction for each of Defendants’

challenged statements.

The SEC’s motion seeks injunctive relief and an asset freeze based on alleged misrepresentations relating to these topics: (1) the compensation of Reven’s Principals from 2019 to 2021, (2) the status of Reven’s plans to obtain audited

22

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 29 of 51

financial statements and go forward with an IPO or DPO, (3) how certain individual investors’ funds would be used, and (4) whether or not certain defendants were the subject of pending litigation. To justify the requested injunction, the SEC must make a “clear showing” that each of these alleged statements were false, material, and that Defendants acted with scienter. Cell>Point, LLC, 2022 WL 444397, at *5. The SEC has failed to meet its burden with respect to each of these elements.

i. Defendants’ challenged statements as to compensation

were not material and not made with scienter.

As detailed above, even using the SEC’s inflated compensation figures, the Reven Principals received far less compensation in 2019 to 2021 than they were entitled to receive under their employment agreements. Greer Decl. ¶ 18 (alleging the Reven Principals made $15,356,779); Ahern Decl. ¶¶ 31-35 (showing that employment agreements entitled Reven Principals to $23.1 million in total compensation for 2019-2021).

After the SEC began its investigation, the Reven Principals became aware that some of Reven’s PPMs included unintentional typographical errors in the sections describing their compensation, including listing incorrect years in compensation tables. For example, the July 6, 2020 PPM states that it shows certain compensation paid “at the end of the last two completed fiscal years.” ECF No. 7-17 at 7 (emphasis added). Yet, the chart below that language lists annual compensation for the years 2019 and 2020—even though 2020 was not yet “completed” as of the date of the PPM. Id. Similar typographical errors appear in the January 1, 2021 PPM. ECF No. 7-20 at 13.

23

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 30 of 51

Defendants understood that the figures in the PPM tables reflected annualized amounts of the monthly draws actually being paid to the Reven Principals, not the total amounts they were entitled to earn under their employment agreements. Volk Decl. ¶ 8. Despite having the express ability to do so under the PPMs, it does not appear that any actual or potential investors ever sought further information or clarification about the Reven Principals’ compensation (as reflected in the PPMs, their employment agreements, or otherwise). Volk Decl. ¶ 8; see also Frost Tr. 123:13– 18, 124:23–25; Schaatt Tr. 115:7–12. Had any investor(s) asked for this information, Defendants would readily have shared it with them. Volk Decl. ¶ 8. Defendants never intended to provide potentially incomplete or inaccurate information to investors. Id.

No Misrepresentation

Setting aside the 2020 and 2021 PPMs, the SEC also relies on certain alleged misstatements related to the expected use of funds in Reven’s 2018 PPM. ECF No. 3 at 12. Specifically, the 2018 PPM outlines Reven’s “estimated use of offering proceeds,” expressly noting that the “planned use of proceeds shown below is subject to change” based on several factors including “actual expenses, changes in general business, economic and competitive conditions, timing and management discretion, each of which may change the amount of proceeds expended for the purposes intended.” ECF No. 9-1 at 31. The SEC appears to imply that listing an estimated figure for its “General Administrative and Payroll Operating costs,” but then later incurring higher actual costs, somehow equates to securities fraud. ECF No. 3 at 12. Not so. The SEC has not (and cannot) show that the expected use of proceeds was

24

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 31 of 51

“false at the time that the document containing it was created.” Goldstone, 952 F. Supp. 2d at 1196 (citing Grossman, 120 F.3d at 1124). Indeed, the document itself states that the amounts “are estimated to the best of our knowledge,” and the SEC has not presented evidence to the contrary. ECF No. 9-1 at 32. No misrepresentation occurred as to the 2018 PPM.

Not Material

The SEC also fails to clearly show that any alleged misstatements were material. Each of the statements relied on by the SEC came with disclaimers about forward-looking expectations and management’s discretion regarding the use of funds, and specifically explained that any potential investor could “obtain additional information and/or documents in connection with making an investment decision.” See ECF No. 9-1 at 4-5; ECF No. 7-14 at 2; ECF No. 7-18 at 2. Notably, no investor or potential investor was ever denied access to the employment contracts or information about compensation; such information would have been provided if requested. Volk Decl. ¶ 8; see Ex. 4, Decl. of Bill Luther, ¶ 7 (“I always felt the Founders were an open book in providing information.”). But no investor was ever particularly interested in the compensation of the Reven Principals. Volk Decl. ¶ 8; see Ex. 5, Decl. of Geoff Leopold, ¶ 6 (“I did not have any discussions with the Founders regarding their compensation prior to investing; from my perspective, their compensation did not impact my decision to invest.”); Luther Decl. ¶¶ 8–9. Even the investors the SEC has relied on to establish materiality confirmed that compensation was typically not a factor they considered when investing in Reven. For example, Frost testified that she

25

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 32 of 51

did not remember having any understanding of the Reven Principals’ compensation when she invested and that she never requested compensation information from the company. Frost Tr. 123:13–23. Thus, Reven’s own investors confirm that the compensation disclosure the SEC points to is not information that was important to investors when deciding whether to invest.

No Scienter

The SEC also has not shown that Defendants made any alleged misstatements with scienter. As detailed above, with respect to the PPMs, Defendants understood them to reflect the annualized amounts of monthly draws then being paid to the Reven Principals. Recognizing that it does not have evidence reflecting intentional (or even sufficiently reckless) conduct for the purported misstatements, the SEC seeks to minimize its burden on scienter. It claims that it can rely on the fact that the Reven Principals purportedly received compensation beyond the disclosed amount to establish the requisite intent to deceive. See ECF No. 3 at 32 (citing, e.g., Centra, Inc. v. Chandler Ins. Co., Ltd., 229 F.3d 1162 (10th Cir. 2000)). But, as detailed above, the compensation paid to the Reven Principals was well within the amounts covered by their Employment Contracts. In other words, there was no misappropriation. And without misappropriation, the payments alone cannot establish scienter. Doing so would improperly conflate the misrepresentation element with the scienter element in every case involving a representation about compensation. The Court should reject the SEC’s attempt to side-step scienter.

26

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 33 of 51

ii. Statements regarding preparing to take Reven public.

Defendants began the multistep process of preparing Reven for a financial audit and potential public offering in 2018, when they completed a corporate reorganization, and continued to work toward these goals throughout 2019, 2020, and 2021. Volk Decl. ¶¶ 9-15. To be eligible for a direct public offering (“DPO”), Reven had to file tax returns, obtain audited financial statements, prepare an S-1 registration statement with the SEC, obtain a third-party valuation, and meet certain market targets, among other things. And before Reven could file tax returns or complete an audit, it had several more steps to complete. Id. ¶ 9. In addition to establishing a register of shareholders, for instance, Reven’s bookkeeping records needed to be reconciled, a considerable undertaking. See id.; ECF No. 13 ¶ 4.

Between 2019 and 2021, Defendants took several steps to pursue their goals of completing an external audit and moving toward a public offering. In 2019, Reven contacted Eide Bailly LLP (“Eide Bailly”), a CPA and business advisory firm, to begin working to reconciling Reven’s books and pursuing an audit. Preston Decl. Ex. K, Deposition of Rodell Rudolph Transcript, 14:23–15:3. Defendants also engaged a vendor called CARTA to properly document shareholders and communicate with them consistently, started to formalize their accounting procedures and processes, and initiated relationships with institutional and investment firms in the biotech and pharmaceutical space. Volk Decl. ¶ 11. In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many of Reven’s plans, yet Reven continued to make progress toward its goals, including by engaging Jeff Halverson as its CFO and tasking him with helping complete tax returns for Reven and its related entities in preparation for an audit.

27

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 34 of 51

Id. ¶ 12; ECF No. 13 at ¶¶ 1-2. Reven also contacted a number of additional firms— including Stifel Healthcare, which generated work product for Reven in late 2020— to begin working together on a potential public offering. Volk Decl. ¶ 13.

In early 2021, Halverson resumed conversations with Eide Bailly to discuss preparing tax returns for Reven and its related entities. ECF No. 13 ¶¶ 3, 5. In particular, Halverson told Eide Bailly that Reven would engage it to prepare an audit once Reven’s tax returns were finalized. ECF No. 13-1. In the following months, Halverson gave Eide Bailly access to Reven’s QuickBooks and provided other information so that Eide Bailly could complete Reven’s tax returns and help Reven prepare for an audit. ECF No. 13-5 at 2; Rudolph Tr. 45:9–22, 47:14–16. That summer, Reven also hired 180 Accounting to help reconcile its bookkeeping records in advance of a financial audit. Volk Decl. ¶ 14.6 In late 2021, Reven also began working with VMLY&R, an advertising company, to create some of the public

offering-focused slide decks the SEC attached to its TRO Application. Preston Decl. Ex. L, Deposition of Brian Denomme Transcript, 211:15–19.

Each of these steps resulted in incremental progress toward Defendants’ goal of obtaining audited financial statements for Reven and, potentially, pursuing a public offering. In short, by the end of 2021, Reven had worked with SEC counsel, established a shareholder register in CARTA, engaged multiple external consultants to help develop financial controls and procedures, hired a full-time staff member to

6 Currently, Defendants believe that 180 Accounting’s work is either complete or near complete, but the asset freeze has prevented Defendants from receiving the benefit of this work because they have been unable to pay 180 Accounting and obtain its work product. See id.

28

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 35 of 51

organize its books, held dozens of meetings with institutions, and contacted representatives of reputable audit firms (including Grant Thornton) about a potential external audit. See Volk Decl. ¶ 15.

No Misrepresentation

The SEC has not clearly shown that Defendants made false and misleading statements and omissions to investors about obtaining a third-party audit and otherwise preparing Reven for a direct public offering. See ECF No. 3 at 29–32. Throughout this process, Defendants made forward-looking statements to investors about the steps they were taking, or planning to take, to accomplish these goals. The vast majority of the statements that the SEC now attacks as misrepresentations fall into this category. But these statements did not, nor were they intended to, communicate with exact certainty a timeframe for completing certain specific benchmarks. Rather, Defendants frequently used forward-looking expressions to communicate plans that were in progress—and that Defendants sincerely believed were feasible. See Volk Decl. ¶ 16; Ex. 3, Decl. of Peter Lange, ¶ 2. For example:

∙ In an email to Schaatt dated November 10, 2019, Mr. Volk noted that Reven was “eagerly hopeful that we are able to close on at least one of the financing options by the 15th of November” and that Reven was “get[ting] closer” to completing an S1 “sometime in January.” ECF No. 9-4 at 1 (emphases added).

∙ In a slide deck sent to potential investors on April 20, 2020, Defendants provided possible exit strategies, one of which included organizing and executing an initial public offering after October 1, 2020. ECF No. 7-23 at 16. In outlining that exit strategy scenario, Defendants proposed that Reven “will have the minimum required two years of audited financial statements . . . to offer its shares for sale in an Initial Public Offering as early as October 2020.” Id. (emphases added). Notably, the slide deck included a disclaimer that its forward-looking statements “involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other important factors

29

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 36 of 51

that could cause the actual results, performance or achievements of the Company, or industry results, to differ materially from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements.” Id. at 5.

∙ The July 6, 2020 PPM stated that an initial public offering was anticipated within the next year but expressly noted that “there are no assurances that we will file for the initial public offering.” ECF No. 7-14 at 8 (PPM page 3).

∙ In an email to Schaatt dated July 8, 2020, Mr. Lange stated that Reven’s audit “should be completed in mid-September early October which will allow us to file our S1 sometime before the end of the year and taking next steps towards an IPO in 2021.” ECF No. 9-6 at 1 (emphases added).

∙ In an email dated July 14, 2021 to Schaatt, Mr. Volk mentioned that they were looking to “raise the final funds prior to our Direct Public Offering.” ECF No. 9-8. In that email, Mr. Volk attached a Pre-Direct Public Offering Brief and Deal Structure, which provided that Reven is “currently preparing for a Direct Public Offering of their stock for a major stock exchange to occur September/October 2021” and that Reven “intends on filing its S-1 registration statement as early as August” but had not yet completed a financial audit. Id. at 2 (emphases added).

In arguing that Defendants intentionally misrepresented facts to investors, the SEC largely ignores the express disclaimers and qualifications that permeate many statements it challenges. For example, the SEC suggests that a June 9, 2021 email from Mr. Lange to Frost was misleading because it discusses a potential DPO in September 2021 even though Reven had not yet filed an S-1 statement or commenced its financial audit. ECF No. 12-2. But that email also specifically says: “The timing is subject to several variables, but we are pushing to achieve our listing sometime at the end of August or early September depending on market conditions and the completion of some of the preparatory tasks that are in process now.” Id. at 2 (emphases added). After reading these qualifying statements, no reasonable investor would come away

30

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 37 of 51

from Mr. Lange’s email thinking that a DPO in September 2021 was a certainty. See also Frost Tr. 104:22–105:13 (agreeing that Mr. Lange’s June 9, 2021 email stated that preparatory tasks for a public offering, such as obtaining audited financial statements, were in process, but Reven had not yet obtained audited financial statements as of June 2021).

The SEC also makes much of statements in slide decks circulated in November and December 2021 that “[t]he company has the minimum required two years of audited financial statements ending August 2021.” ECF No. 12-7 at 22; ECF No. 9-9 at 19; ECF No. 9-11 at 22. This statement, however, was included to describe one of three possible scenarios for Reven’s future. See, e.g., ECF No. 9-9 at 22; see also

Denomme Tr. at 214:15–216:10 (explaining the slide to mean that Reven will have audited financial statements “[w]hen we organize and execute the initial public offering”).7 Further, the SEC does not (and cannot) argue that either Schaatt or Frost relied on these slide decks when they invested in Reven, because their investments all pre-dated the relevant emails. See ECF No. 9 ¶¶ 29–49; ECF No. 12 ¶ 18. Indeed, the evidence supports Mr. Denomme’s testimony that the real purpose of this slide deck related to Reven’s planned meetings with outside institutions, not individual investors. See ECF No. 9 ¶ 29 (noting that Mr. Lange told Schaatt that Reven was

7 To further illustrate this point, the same slide contains a separate “Organic Growth” scenario in which Reven would continue to grow through selling and marketing RJX and derivative products. ECF No. 9-9 at 22. That section of the slide states: “Margins built into the pricing of the product are substantial”—even though, to this day, Reven has not yet begun selling or marketing any RJX products. Id. (emphasis added).

31

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 38 of 51

sending the deck to “institutions they were speaking to”); ECF No. 9-11 at 1; ECF No. 12 ¶ 16; see also Denomme Tr. 211:15–19, 213:1–11.

Testimony also confirms that investors believed “that financial statements were in the process of being prepared and finalized,” not that they already existed. Schaatt Tr. 63:19–64:5; see also id. 101:11–24 (confirming Schaatt’s understanding that Reven had not filed an S-1 for the current offering as of July 2021). As demonstrated above, there is no dispute that Reven and its Principals were then working through this multistep process. Accordingly, no misrepresentations occurred.

Not Material

The SEC also has not clearly shown that any alleged misstatements were material. As noted above, some of the statements relied on by the SEC came with disclaimers about forward-looking statements or obviously contained mere predictions of future events. In other instances, later communications show that Defendants provided more complete information, rendering any earlier misunderstanding immaterial. For example, the SEC claims that Mr. Lange misrepresented to Schaatt in a February 2020 email that Reven had already filed an S-1 statement, but two different communications to Schaatt in July 2020 made perfectly clear that this had not happened yet. Compare ECF No. 9 ¶ 15, with id.

¶¶ 18–19.8 see also Schaatt Tr. 101:11–24.

8 Schaatt did not invest in Reven between February and July 2020. See id. ¶ 21.

32

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 39 of 51

At times, Frost and Schaatt also conceded that they did not rely on the statements at issue when they invested. Frost, for example, agreed that she did not rely on any promise that Reven would pursue a DPO when she invested in 2020. Frost Tr. 74:8–13; see also id. at 73:14–17 (declining to testify that Reven promised to do a DPO); id. at 102:10–24 (agreeing that the DPO described in Mr. Lange’s June 9, 2021 email was a plan that could change). What’s more, other investors confirm that they understood that a public offering was possible, but by no means guaranteed. See

Luther Decl. ¶ 10; Leopold Decl. ¶ 7. Thus, the evidence does not clearly show that investors reasonably relied on statements about the planned timing for a public offering in deciding whether to invest in Reven.

Any alleged misstatements also were not material considering the record evidence showing Defendants’ consistent willingness to answer questions from, and provide additional information to, investors. See Frost Tr. 101:14-21; Luther Decl. ¶ 7; Leopold Decl. ¶ 5. Schaatt, for example, did not follow up with Reven to ask for copies of any financial statements (even unaudited financial statements) or Reven’s potential S-1 filing, despite being an experienced financial professional herself. Schaatt Tr. 72:5–22, 73:12–74:6, 80:8–11, 108:25–109:2. She also conceded that she generally knew that financial statements for a “start-up, no revenue company” like Reven “would not be very robust.” Id. at 31:12–15, 31:23–32:1. This testimony calls into serious question whether any alleged misrepresentations about the timing of Reven’s audit were material. Considering these facts, the SEC has not clearly shown materiality.

33

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 40 of 51

No Scienter

The SEC also has not shown that Defendants made any alleged misstatements with scienter. To the extent the SEC claims that Defendants misrepresented that Reven already had audited financial statements, the SEC’s own documents include numerous examples of Defendants telling investors the opposite. E.g., ECF Nos. 9-6 at 1, 9-8 at 1, 12-2 at 2-3. And Mr. Volk confirms that he never intended to misrepresent to investors that Reven had already begun an independent audit. Volk Decl. ¶ 18.9 Nor can the SEC clearly show scienter based on sincerely believed statements that Defendants made about future plans to pursue a public offering or obtain audited financial statements. Volk Decl. ¶¶ 16-18; Lange Decl. ¶ 2. For these reasons, the SEC has not clearly shown any violation with respect to these statements.

iii. Statements regarding use of funds.

The SEC also challenges certain statements Defendants allegedly made about the use of investor funds. Namely, the SEC challenges: (i) a September 2019 email from Mr. Lange to Schaatt in which Mr. Lange sent a spreadsheet allegedly listing certain expenses; (ii) alleged statements in July, August, and September 2021 about using investor funds to work on clinical trials and progress toward a DPO; and (iii) alleged statements to Frost in September 2021. But, as explained below, Defendants used investor funds in substantially the same ways they represented to

9 Likewise, even if Schaatt misunderstood Mr. Lange’s February 2020 email to mean that Reven had already filed an S-1 statement, Mr. Lange did not intend to make any such representation. Lange Decl. ¶ 5.

34

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 41 of 51

investors that they would—and, in any event, any alleged misrepresentations could not have been material given the express disclaimers about the use of investor funds in Reven’s PPMs. For these reasons, the SEC has not clearly shown violations based on the use of investor funds.

No Misrepresentation

The SEC’s attempt to make a clear showing of misrepresentations relating to the potential use of investor funds fails, as a threshold matter, for the simple reason that those funds were used in substantially the same ways as represented to investors. For example, Schaatt wired Reven funds on September 13, 2019, and claims she was told on September 16, 2019 (after her payment to Reven) that her investment would be used to pay a number of vendors and employees. ECF No. 9, ¶¶ 9–11; ECF No. 9-3 at 2. Indeed, by September 16, Reven had made payments to at least 12 of the 16 categories of recipients listed on the “use of funds” document, including substantial payments to a number of employees. Compare ECF No. 9-3 at 2, with ECF No. 54, Ex. A to Reven Entities’ Decl., at 16–17. At least one more category was paid later. See ECF No. 54, Ex. A. to Reven Entities’ Decl., at 22. What’s more, Schaatt invested $2 million, yet the spreadsheet lists only $1,380,441.87 of expenses in the “To Pay” column. ECF No. 9-3 at 2. Accordingly, it should have come as no surprise to Schaatt that Reven used some of her funds to pay other expenses not expressly included on the spreadsheet. See Schaatt Tr. at 52:18-22 (acknowledging that the spreadsheet showed how approximately $1.38 million of her investment would be used); see also id. at 171:11-19.

35

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 42 of 51

Similarly, Green claims that Volk represented to him that his funds would be used to “complete phase II trials in process, do more phase II trials for the drug, and to complete the necessary steps to go to a DPO.” ECF No. 11 ¶ 6. Sure enough, the day after Green wired funds to Reven Holdings on September 15, 2021, those funds were transferred to Reven’s working account, and Reven made a substantial payment to PRX Research, a clinical research facility involved with the Phase 2 trials. ECF No. 54, Ex. A to Reven Entities’ Decl., at 62; Volk Decl. ¶ 23. Later that month, Reven continued to use funds to pay ordinary course expenses, such as salaries; and, as Schaatt conceded, such expenses can properly be considered part of the process of completing Phase 2 trials. Schaatt Tr. 117:14-22. Accordingly, these statements were not misrepresentations, as the funds were primarily used for the reasons conveyed to investors.

As for Frost, the SEC argues that Reven misrepresented the intended use of her and her family’s funds by telling her that investments made on September 24, 2021 would be used for a licensing transaction when, in fact, Reven made the sole licensing payment on September 16, 2021, before the investments were received. ECF No. 3 at 20. But Frost testified that it was her understanding that Reven did use her investment to pay the licensor, Reven’s then-chief medical officer. Frost Tr. 156:19-

157:4. Even setting that aside, the SEC ignores the fact that all the alleged communications from Defendants to Frost about the payment occurred before September 16. See ECF No. 12 ¶¶ 10–13 (describing communications on September 1, 8, 10, and 13, 2021). The emails also show that Defendants told Frost that the

36

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 43 of 51

proposed licensing transaction was time-sensitive and needed to occur no later than September 15. See ECF No. 12-3 at 1–2 (“We want to ink this transaction with Dr. Uckun before the 15th of September[.]”); ECF No. 12-4 at 2 (noting the need to pay $8.5 million “in the next 6-7 days” after September 8). Based on these communications, Frost had no reason to believe that by the time she and her family invested money on September 24, 2021, Reven still planned to use her funds on the proposed licensing transaction. See also Frost Tr.148:21-151:13 (testifying she could not recall if Mr. Lange told her how much had been raised for the license or what would happen if the full amount could not be raised). Thus, once again, Defendants did not misrepresent the use of the Frost family’s funds.

What’s more, any statements about specific uses of funds were meant to reflect Reven’s immediate expenses, not a guarantee that investments would be used for a specific purpose. Other investors asked or were informed by the Reven Principals “what payables or foreseeable payables were coming up,” “what specific payments were due[,] and what vendors needed to be paid.” Luther Decl. ¶ 6. At a minimum, other investors understood “that the funds would help move Reven along,” and “never received or asked for specific representations on how my funds would be used.” Leopold Decl. ¶ 8. While specific statements relating to the use of funds represented the general direction Reven was heading, which expenses needed to be paid, and the Reven Principal’s intentions at the time they were made, investors understood that more pressing business needs could always arise.

37

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 44 of 51

Not Material

PPMs and other disclosures made clear that Reven had broad discretion to use investment funds as it deemed appropriate. The PPMs contained a disclaimer with the heading, “We have broad discretion in the use of proceeds of the Offering.” See, e.g., ECF No. 7-15 at 13. In this section, the PPM further stated:

After deducting estimated Offering expenses, a significant portion of the net proceeds of this Offering will be going towards working capital and other general corporate purposes. Accordingly, our management will have broad discretion as to the application of such working capital. The proceeds shall be used to carry out our business plan, compensate our employees and consultants, and satisfy all our expenses, foreseeable and unforeseeable. As is the case with any business, it should be expected that certain expenses unforeseeable to management at this juncture will arise in the future . . . Our management may utilize a portion or all of the proceeds of the Offering on expenditures with which you do not agree.

Id. The PPMs make clear that proceeds would be used as needed by Reven, even potentially in ways “with which [investors] do not agree.” Id. Even prior versions of the PPM, including the version purportedly relied upon by Schaatt, state:

The planned use of proceeds shown below is subject to change based on the actual net proceeds received from this Offering, actual expenses, changes in general business, economic and competitive conditions, timing and management discretion, each of which may change the amount of proceeds expended for the purposes intended.

ECF No. 9-1 at 31 (emphases added). These disclosures therefore disclaim any reliance by investors on statements made by the Reven Principals.

iv. Statements regarding Florida litigation.

In August 2016, Dawn Van Beck, court-appointed guardian of a former Reven shareholder, initiated a lawsuit in Florida state court. See Preston Decl. Ex. A. The initial defendants were Reven Pharmaceuticals, Mr. Lange, and two non-parties to

38

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 45 of 51

this litigation. See id. In June 2017, Beck amended her complaint. See id. Ex B. At that point, she alleged five causes of action against the same four defendants: sale of unregistered securities, securities fraud (under Florida state law), common law fraud, unjust enrichment, and exploitation of the elderly. See id. at 6–10. A few months later, the court dismissed the securities fraud, common law fraud, and exploitation of the elderly claims. See id. Ex. C.

In December 2017, Beck filed a Second Amended Complaint alleging the same causes of action (except exploitation of the elderly) against the same four defendants. See id. Ex. D at 7–11. It was not until two years later, in December 2019, that Marie Renton, who succeeded Beck as guardian, filed a Third Amended Complaint naming additional defendants, including Reven, LLC. See id. Ex. E. On June 22, 2020, the Court dismissed two counts of the Third Amended Complaint without prejudice. See id. Ex. F. On July 6, 2020, a Fourth Amended Complaint was filed, and the case was eventually settled. See id. Ex. G.

No Misrepresentation

The SEC predicates liability on alleged misstatements about this lawsuit included in three documents: (1) an August 31, 2018 PPM; (2) an email from Mr. Lange to a shareholder dated February 13, 2020; and (3) a July 6, 2020 PPM. But none of these statements rises to the level of being materially false, let alone intentionally misleading.

First, the August 31, 2018 PPM was issued by Reven Holdings, Inc., a non party to the underlying litigation. The PPM defines the Company as “Reven Holdings,

39

Case No. 1:22-cv-03181-DDD-SP Document 96 filed 06/12/23 USDC Colorado pg 46 of 51